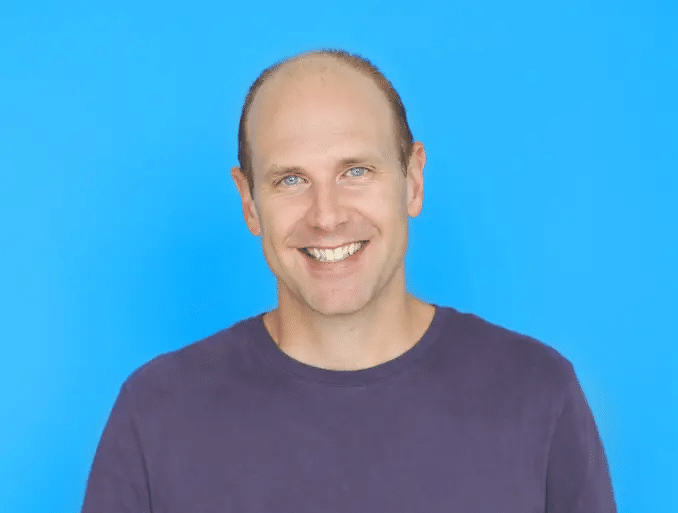

Mike McDerment is the co-founder and CEO of Freshbooks which is a cloud-based accounting software that allows owners to invoice clients, track time and run their small businesses in the cloud.

In this episode you will learn:

- How to use your time and the clock during an investor pitch

- Why the Q&A is such an important part of pitching investors

- The truth about being a startup founder

- How to get your 30 day free trial of Freshbooks

SUBSCRIBE ON:

For a winning deck, take a look at the pitch deck template created by Silicon Valley legend, Peter Thiel (see it here) that I recently covered. Thiel was the first angel investor in Facebook with a $500K check that turned into more than $1 billion in cash.

*FREE DOWNLOAD*

The Ultimate Guide To Pitch Decks

Moreover, I also provided a commentary on a pitch deck from an Uber competitor that has raised over $400 million (see it here).

Remember to unlock for free the pitch deck template that is being used by founders around the world to raise millions below.

About Mike McDerment:

Mike McDerment is the co-founder and CEO of FreshBooks, planet earth’s leading online invoicing app for service-oriented professionals, freelancers, and teams.

In 2003, Mike McDerment built FreshBooks for his design firm and scratched his own itch.

Since launching in May 2004, FreshBooks has touched over 800,000 lives. Mike McDerment and his team dedicate themselves to being a great service for people who love their work and want to focus on it instead of focusing on their paperwork.

In addition to FreshBooks initiatives, Mike McDerment is a founder of the mesh conference, lecturer at Humber College and a frequent speaker at conferences, addressing topics such as entrepreneurship, social media, marketing and web applications.

Connect with Mike McDerment:

* * *

FULL TRANSCRIPTION OF THE INTERVIEW:

Alejandro: Alrighty. Hello everyone, and welcome to the DealMakers show. Today we have quite an interesting story. A story of a company that started bootstrapping for quite a while before they ended up going into the hypergrowth scaling and raising money from outside investors and so forth. I think there are a lot of things that we can learn here because this founder has been at it for quite a bit. So without further ado, Mike McDerment, welcome to the show.

Mike McDerment: Thanks for having me, Alejandro.

Alejandro: Originally born and raised in Toronto. How was life there, Mike?

Mike McDerment: We’re in the midst of COVID. We’re the third or fourth-largest city in North America. We’ve pretty much in shut down. Generally speaking, I’m very fond of life in Toronto. I’m a big booster for the city.

Alejandro: Very cool. How was it there? Were your parents entrepreneurs or how did you get that bug? Was there anyone in the family?

Mike McDerment: It’s interesting. Not obviously, is the answer, but I’ll explain a bit further. My dad was certainly involved in the business world. He was a lawyer and a corporate lawyer, but if I could be frank, growing up, I really had no clue what he did. I just knew he would work long hours, and it was great when he was with us, but lots of nights, I’d be asleep well before he got home. My mom was a largely stay-at-home. I’m the fourth kid of four. What was interesting about her was, she always had projects she was working on, and she started a number of things, and they were mostly charitable and volunteer things, but some of them were really interesting. She built a program that she called Transitions. She basically worked with and networked with all these large corporations to help people. The hardest thing about getting a leg-up in the world is often getting your first job. To go to an interview and be presentable and even to have, for example, the right clothes so people wouldn’t judge you by what you’re wearing. This program, Transition, was all about that. She would work with corporates and convince them to at least interview x-number of people. Then she would get donations for literally clothing and do some coaching around interview skills and resume writing, so people have a shot easing the ramp in and have a better shot at getting a role. It was a very successful program. So that’s one thing. She did a couple of other things along these lines. My point of saying all this is, I believe she’s very entrepreneurial, but in perhaps some less obvious ways.

Alejandro: Got it. For you, you spent most of your childhood and time in Toronto, but then you went to school, and this opened up the fact that there was more outside of Toronto. So what did you get out of living in Germany, the U.S., and other places around Canada?

Mike McDerment: That’s good. That’s certainly somebody in our family who never went away for vacation or anything like that growing up. That was four kids and the rest of it — not really in the cards. Yeah. Going to undergrad, I moved away. I went to Queen’s University, which is not far from Toronto, about three hours, and a very, very good school. I studied business there. I got to go on an exchange program for a year to Germany, or not even a year. It was a summer semester, so four months. That was an impactful time and a lot of fun. Then I came back. I had a couple of passions through these years, which were frankly, I became a ski lift operator before I went to University in the Interior British Columbia. [Laughter] Who’s interested in these facts? But you can get into business through these things, apparently a true thing. The other thing was, I got passionate about the sport of Ultimate Frisbee. I had run a couple of little businesses myself organizing tournaments for 600 people and that kind of thing prior to getting into what is more now the vein in my professional life in software and things of that nature.

Alejandro: Of course. Obviously, the business side happened right after school. Here you are, starting to figure out what’s going to be next, what’s going to be there for you. Obviously, law was not the thing — corporate law. Let’s say what you were seeing in your father. You actually opted for consulting, which led into something unexpected. What happened?

Mike McDerment: Yeah. First of all, let’s go there for a while. I always think of your mid to late 20s as some of the worst years of your life because it turns out nobody actually knows what they’re doing, or very few people, but nobody is talking about that fact. We had a next-door neighbor, and she had known me since I was two. I went and paid her a visit, and she was like 70 years old at that point. She laughs at me now. She’s like, “Mike, you could not tell me what you wanted to do, but you sure had a long list of things you didn’t want to do.” We sat there, and in a process of elimination, I just started doing stuff. One of the things was, I mentioned the frisbee tournament, we went ahead and built — I started this frisbee tournament, and I had to teach myself how to build web pages. So I started a small web design shop. As soon as I was building websites for myself, other people started to want them. This is around ’99 to 2000. The caterer from my event business I was running at the frisbee tournament needed a website, so I started building them for others. As soon as I started building them for others, I was like, “What’s the point of doing this unless people show up.” So I got into internet marketing to help draw traffic to sites, and then as people showed up, I was like, “What’s the point if they don’t take the actions you want. I got really early into the conversion consulting stuff, which was a big deal for a lot of consumer websites these days. All that progressed over a number of years, I built a shop. I had some people working regularly on a contract from me. So, pretty much three or four full-time employees, whether they were full-time or contract. Then I saved over an invoice and decided, “This is silly. I’m running my business with Word and Excel.” I studied business in school, but I know I do not want to use the accounting software that’s available today because it’s not built for me as an owner. So I built a simple prototype of an invoicing software, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Alejandro: And this actually happened from your parents’ basement. At what point did you know that this could go into something much bigger than just a testing thing, or there could be a business here?

Mike McDerment: I think pretty soon. We really built it for ourselves. I was living away. I was moving shortly thereafter, back into my parents’ basement, and building the business out for a few years. I was doing freelance work. I was working from my apartment. I built it for myself, and then some of the people I worked with regularly started working on it as a past time. We had a lot of passion around it. The first use case was building for ourselves, which I think is a great thing when you’re starting a business. If you can be or are the customer, it’s a major, major leg-up. But it wasn’t obvious immediately that everybody would want this. Then after a few months, I basically started to develop a mania that everybody needed this thing. Everywhere I looked, they needed it. I was, frankly, out of my mind with how excited I was about the possibilities — having never worked in a big business or anything like that. I didn’t understand what scale looked like or could be. We started out with — I don’t want to say modest, but let’s call it realistic ambitions. I think we’ve conceded to meet or exceed those over the years.

Alejandro: What was that phase like? It seems that you got product/market fit very quickly. Is that accurate?

Mike McDerment: I think we did for early adopters who wanted a certain kind of usable invoicing software and then some very light and basic accounting afterward. I would say we were always very close to the customer, and we did a good job building. Cloud was basically new back then. We were pioneering with building user experiences for business owners in the Cloud.

Alejandro: It’s very interesting here when I hear you talk about user experiences, conversions, using internet marketing. Really understanding those funnels, especially during the early stages when you’re figuring out what you’re selling, how you’re packaging, how you’re positioning, and how you get people in the door. It’s critical. So, what was your biggest learning during that time where maybe a big Aha moment of how to get people faster in the door?

Mike McDerment: I think there were a whole bunch of big learnings in those days. I think going back to the customer and being close to the customer never fails you. Then there’s the question of what are the many ways you could do that? Yes, I had my internet marketing background, which proved to be very helpful for focusing on low-cost acquisition like SEO and all those things to start. But also, there was a bit of a research discipline that emerged where I could go out and just survey people and actually talk to them. I think this has become like the lean startup, and all that stuff, Erik Rees, etc. has become far more commonplace, but that stuff wasn’t around to read about it or learn on or draw from. We got there for first principles. That stuff just never goes old. You cannot spend enough time with your customers, knowing them, understanding them. It’s like motherhood and apple pie if you want to throw a bad analogy. That stuff never goes old, and it is evergreen. Customer development, I think, was the big thing.

Alejandro: In that regard, what did you learn about asking your customers the right question so that their answer would guide you the right way in terms of product development?

Mike McDerment: That’s a good question because, in my experience, most people do research really, really poorly, and they introduce a whole bunch of bias trying to get to answers that they want to hear. We had the good fortune at this time. We were trying to raise money from an angel group. It was funny. We almost raised $300,000 for 30% of the company back in the day. We would have been happy with that. We didn’t know any better, and those were the times. One of the things that happened from that angel group was one of the angels said, “Listen, I don’t understand your business and if it’s real or not. We can pay a consultant to go ahead and evaluate you folks and effectively look for worms in the apple, or you folks could pay for them and get some of the benefits out of it.” This guy’s name was Bob Lord. It turns out he was the head of Ernst & Young in Canada and Cherub, the accountant’s thing. We found our way to a really interesting angel. I’ve got to say, that was such a magnanimous approach because we ended up working with this consultant. He taught me a ton of stuff, like how to do structured research. For example, instead of asking a question where it’s a yes/no answer, how do you design a question that’s open-ended in nature and where the person could go any which way? You just give them the space to go and do that. That is a small and subtle thing, but it is night and day difference in terms of what you get back from customers. Instead of asking, “Do you like this?” which is like, “Yes, I do.” That’s just not that helpful. Ask, “What would you recommend to perform this kind of job?” That might be a bad example, but you get the spirit of things. It really changed the quality of the stuff we got back, and frankly, how fast we learned.

Alejandro: Obviously, that’s for the qualitative data. For the quantitative data, did you guys have any systems in place to understand the user behavior and patterns? Or, perhaps at that point, there was not much available.

Mike McDerment: What I would say there is, I think we were quantitative on the marketing acquisition side, and we were qualitative on the product development side. But we spoke to enough customers, where intuitively everyone on the team would know the priority. Like, we would have 30 things everyone wanted to build, but I went ahead and chose the three I thought would be most impactful. Everyone would nod their heads because if we’re spending all the time with the customers, we intuitively knew those things to be true. That’s, I think, how we did the product development. There wasn’t really much quantitative is the punchline, other than like support tickets and how many people have been writing in, but even that was pretty intuitive as well.

Alejandro: Here, you’ve been at it for quite a while, for 17 years, which is remarkable. But the first ten years of the business, you were really opposed to venture capital. Why was that the case?

Mike McDerment: Yeah, it’s true. I like to call myself the poster boy for the anti-VC movement. [Laughter] I was very standoffish. If you scratch underneath what was behind that, it’s because I knew I was so gapped from what the whole venture game was. So I think it was two parts. One, I knew I didn’t know. But also, I think there were also a lot of bad behaviors that were happening. For anyone who was around in the early to mid-2000s, and if you think about venture capital, I think it got its nickname vulture capital at that time. There was this massive information arbitrage between the entrepreneurs and the investors. You could argue there still is today, but I’ll tell you, it is nothing the same, and I’ll explain why in a second. I knew I was so outgunned on this stuff. We said, “I’d rather not deal with the devil and just keep going and figure out a way to do that.” That was one part of it. Another part of it was, I was operating out of fear. Fear, in the sense that I was really concerned the capital and the investors would change our culture and the way we served our customers and which customers we served. I’d effectively lose control over what I think of as the spiritual questions of the company. I was concerned about that happening and happening quickly because I didn’t have the first clue around how all this high-finance stuff worked. I think those were the things behind my thinking. We kept on going and found ways to get by. We ended up some angels took an interest, so we raised $50,000 here, $100,000 there. Our business model was subscription-recurring revenue. That was all-important because the business model just consumed so much capital. Then we worked hard at all the dollars we had, and we worked the heck out of. I remember buying ads on Hot Scripts, which was a website that was a software directory for $300 to $400 a month and measuring them down. Then you get to this place where we knew back then that it cost us four months of revenue to get a customer. We just had no idea if that was good or bad. Any VC day would be like, “That is incredible. Let me pull out my checkbook” because they stick around for multiples and multiples of that. Those were the early days. The information wasn’t there. We didn’t have any benchmark; we didn’t have anything. Along came the internet. Information arbitrage has been — the two sides of entrepreneur and venture capital have been brought back together. That has actually made it really hard to behave super badly. It’s also helped all the entrepreneurs raise their game, so the folks who are investing have better, stronger entrepreneurs to invest in that are more aligned with what they’re trying to do. For all those reasons, we didn’t get into it. Over the next ten years, I took the calls all the time. I would ask the questions, and I would try and start to understand that different people have different check sizes. Some people invest in growth. Other people want profits. I started to profile and understand the various kind of investors out there, and also start to figure out which people. Is this just math? And which people actually want to build something and understand working alongside people who do. I think that was valuable when it came time to raise capital and to know who do we really want to work with?

Alejandro: In this case, what ended up being the business model of FreshBooks, especially for the people who are listening?

Mike McDerment: FreshBooks, by the way, is really ridiculously easy-to-use invoicing and accounting software in the Cloud. Our big innovation is, we’re built for owners instead of accountants, so it’s very intuitive. It’s very easy to use. Further to that, and probably the reason we get to keep it that way is, we don’t serve retail. We don’t serve restaurants. We’re built for service-based businesses, so folks who get billed and paid for their time and knowledge and expertise, and/or some subscription kind of stuff and sales. That’s what we are. I’ve actually forgotten your question. That’s what FreshBooks is for those that don’t know. What was the question again?

Alejandro: I was just asking about the business model. You answered that very well. Obviously, now, as you were building and scaling the business, in 2008, there was a moment that was pretty nerve-wracking. You were counting on some money that ended up not coming through. Tell us the story.

Mike McDerment: Sure. I’ll answer your question because I got away from it. We are a subscription-recurring revenue business. We started that way from the outside. I don’t think we appreciated what a good model that was at the start, but we were selling over the internet. It didn’t make sense to do a one-time license. But it was pretty lean for a long time. I’ll just go ahead and say it, most places. We attend customers after two years, and they’re paying us $9.95 a month each. So, we’re making $100 two years into this project. So, when I say it was lean, I mean it was lean. Your question was around 2008. The $100 was the end of 2004. We built up, and we got to a few thousand customers. 2008, we were working with an angel. It was October 2008. We had all the details of the investments sorted out. It was all set to go, and then 2008 happens. I wasn’t really worried. I was like, “Ah, it’s all going to be good. This thing’s going to close,” etc. He called me back, and he was like, “Listen. Here’s my deal. I’m greatly affected by this whole thing. I don’t think I can actually get you the capital to a degree.” He ended up doing some of it, but he was like 40% of what he was thinking before. We had basically started operating as if that capital was there and kind of banked. We basically were staring down the barrel of are we going to go bankrupt? And all these other things. We had to hunker down. The good news is, we had this recurring revenue model. We had no idea how to go ahead and forecast what a recession would do to a business like ours. We made some stuff up. We spent a bunch of cycles, my co-founder and I, in a room modeling. Long story short, we came up with something and got out of there. We had actually never done this before. We had to let go of two people. We were only 26 people, so we went down to 24. We had some salespeople who were like, “You can go if you want. If you stay, it’s going to be a little more commission-based, and you’ve got to figure out. We’ll know what the numbers are, and we can tell you, we’ll all see it coming from a mile away. If we have to do something more drastic, do you want to go and stay with us?” They said, “Yes, we do.” A long story short, we made it through that. We ended up growing 180% the next year. This is the hard thing about businesses that are early stage. Pulling your growth rate down has massive implications on your planning and forecasting. It’s not that you’re not growing; it’s you’re not growing to the same degree is the concern. It’s a nice place to live relative to a lot of mature businesses. That was our concern. We ended up making it through. Then, interestingly, a few years later deciding, “This is kind of boring. Maybe we should raise some capital and take it to the next level.”

Alejandro: Got it. Here, you have a pretty interesting experience that you can apply to the times that we’re living in, with the coronavirus and all this uncertainty. You saw what happened with the dot-com bust. Then you also went through and lived through the 2008 Great Recession. Now, you’re also getting to live through what’s happening now with COVID. I think that history repeats, so how are you thinking about this, and having that background experience of dealing with uncertainty?

Mike McDerment: Over the years, tons of uncertainty, but specific to these scenarios, in a roundabout kind of way, I guess I’m very grateful for having seen 2008. It gives me a measure of hopefully, not falsely-placed confidence for how our business will behave. I could be very, very wrong at the end of the day. We’re all trying to understand what are the knock-on implications of COVID and people being at home and for a long period of time. What are the real implications of this? I would say, for our business, it’s incredibly good fortune, for which we’re grateful. As I said earlier, we don’t serve retail. We don’t serve restaurants. So, we’re services-based. Our segments are relatively less impacted by this, or certainly not as drastically impacted. We do have customers that are, for sure, and that’s very hard, and we’re trying to work with them where we can. We’re relatively sort of better off, so we have a pretty good idea of what we think the next little while will go like. What we don’t know how long people will literally be self-isolating. Frankly, I’m based in Canada. We’re pretty locked-down. Parts of the states are. I know parts of the states still are not, and whoof, that’s a different conversation, and probably has knock-on effects that maybe we’re underappreciating because of how we’ve behaved here. I don’t know. New York is basically trending up the peak cases line right now. It’s just so unsettling, to say the least. We’ll see. That time historically helps me, for sure, as an entrepreneur, and I think we’ve got a good outlook and a good approach to dealing with these times.

Alejandro: Got it. As part of this, as well, I wanted to ask you. You guys have ended up raising quite a bit. How much capital have you guys raised to date?

Mike McDerment: I don’t know if we’re fully disclosed, but let’s call it on the order of 100 million dollars, somewhere in and around there.

Alejandro: Okay. It took you guys a little bit of time to get out there and start going into hypergrowth, financing cycle after financing cycle. Can you walk us through that experience perhaps from the moment that you told yourself, “Oh, perhaps VC is not so bad”? And then how it went over time with raising the different rounds of financing?

Mike McDerment: Yeah. I think a couple of things in there. Yeah, we raised a little bit of angel capital. Then 2014 was the first time we raised what I call institutional capital. I raised 30 million dollars from a series of really great investors back then. All that time, being selective about who we work with. It has paid huge dividends. We raised a round there. Then in 2017, we raised a round and had a bunch of outside interest, but the insiders were even more bullish, so we worked with them again. Then early last year, 2019, J.P. Morgan Chase joined the cap table. That is the history. So, kinda, gonna, done, inside, strategic, first raise, all these kinds of things. Anyone who has raised capital has stories from doing that. If you’re pitching in the Valley, and you’ve got three or four pitches a day, every place you go, you get a water bottle. It’s like, “Oh, of course, I’d like a water.” I don’t want to be rude and turn that down. You use the toilet 100 times that day. Everything to the mistakes made along the way. I think one of the best things I got, and I even learned this from myself. There’s a guy, Steve, at FT Partners, who is well-known through the investment bank, but he was nicely, “Wow. I wish I’d learned this sooner,” how you use your time in the pitch. Fundraising is a process. There are many phases in it, and it starts before you ever pitch anybody. We go ahead and talked about all the parts of it. But I think one nugget I’d love to impart to people, which is less a story for me — I could turn it into a story. Here we go. I was having dinner with Steve, and he told me this, and I was like, “Oh, my gosh. Why didn’t I know this before?” When you think about having an hour to pitch to people, I remember pitching people basically to the last ten seconds, so there was no time for Q&A. If you put yourself in the shoes of somebody who is an investor, first of all, you’re just not that interesting. I have to sit through 100 of these a week, probably, but that’s an aside. I mostly held people’s attention, I think, but I didn’t leave any room to ask questions. You want to leave time to ask questions because you want to a) Build a rapport. They want to see how you respond to questions. b) Understand where they’re coming from. So as an entrepreneur, you’ve got to understand that. What are they really hunting in? What are their concerns about this kind of business and business model? For a whole variety of reasons, you want to allow a little time for Q&A. The other thing I didn’t do is, I’d always pitch the historical. Looking back, we could solve a better culture, this is all a better product, this is a better offering, this is the historical financials, and not nearly enough time with “If you write a check, here’s what I’m going to do with it, and why that’s going to be awesome.” I think you want to swivel the time. Steve broke it down. But you want to spend like five to ten minutes quickly updating people on the historical. Then like 10 to 15 on what you’re going to use the capital for and get to a discussion as fast as you can. That was a bit of a revelation for me, and I think for a lot of aspiring entrepreneurs, how you use the time and manage the clock is not obvious.

Alejandro: That’s very interesting. Obviously, it makes sense because fundraising is all about addressing concerns. Concerns are really what separates you on the money. So the more that you talk, the more that you’re not allowing the investors to ask the questions, and the less time you have to address concerns. So it’s all about listening more than talking. That’s why we have two ears and one mouth. So, Mike, let me ask you this. How big are you guys today? You have quite a bit of employees.

Mike McDerment: We’re about 400 give or take. About 20 million people use the software since we started, and we have paying customers in over 100 countries.

Alejandro: Very cool. How do you see your space as a whole? Where do you see it heading?

Mike McDerment: Well, I think we’ve got some remarkable dynamics across the world with small business needing more and more technology being accessible to them from both a price and usability standpoint, and it being increasingly important for small businesses to have the — I’m trying to avoid the word leverage, but just the utility and the organizational improvements that you get from using technology. So they are big needers and consumers thereof. I see a lot more of that. Things moving to the Cloud. More products working together. FreshBooks is a platform. We have hundreds of developers who have gone ahead and built into what we do to help better serve our customers. I think that is all Net Positive for people who use our software.

Alejandro: Very cool. Very cool. One of the questions that I typically ask the founders that come on the show is — I mean, you’ve been at it, Mike, for 17 years. Oh, my gosh, the amount of lessons and experiences. If you had this chance, Mike, of going back to that basement of your parents and having a chat with your younger self, that younger self that was looking at what’s possible? What’s next for me? What kind of business can I build? If you had that chance of going back then and having a chat and giving your younger self one piece of advice before launching a business, what would that be, and why knowing what you know now?

Mike McDerment: It’s funny. I always try to come up with a better answer to this, but I’d be terrified to talk to that guy because if I tried to tell him what it was going to be like, there’s no way he’d go on the journey. Because it’s too much. It doesn’t stop. It’s all these things. But I was in the challenge of personal growth. I still very much am, so I think the main thing would be to try and enjoy the journey. It is thankless, soul-challenging, gut-wrenching, nerve-wracking, and at times very rewarding to go ahead and build a business. I think there’s generally more dark than light. So you’ve got to have a disposition to be able to handle that. But at the same time, those light spots are pretty bright. I think it’s just, try and enjoy the journey, the good and the bad, and recognizing that both are imposters, and just sticking with it.

Alejandro: Very cool. Mike, for the folks that are listening, what is the best way for them to reach out and say hi?

Mike McDerment: If you want to get me directly, probably @mikemcderment on Twitter. Otherwise, you can find us at FreshBooks, where you can do a free trial for 30 days and check us out on the website there. You can get more information about me, too.

Alejandro: Amazing. Well, Mike, thank you so much for being on the DealMakers show today.

Mike McDerment: Okay. Thanks for having me.

* * *

If you like the show, make sure that you hit that subscribe button. If you can leave a review as well, that would be fantastic. And if you got any value either from this episode or from the show itself, share it with a friend. Perhaps they will also appreciate it. Also, remember, if you need any help, whether it is with your fundraising efforts or with selling your business, you can reach me at al*******@**************rs.com.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

Facebook Comments