Childhood friendships rarely turn into billion-dollar ideas. However, for Kelly Littlepage and Stephen Johnson, a shared curiosity in technology formed during their teenage years in suburban Colorado eventually became the foundation for building OneChronos.

OneChronos has secured funding from top-tier investors like 9Yards Capital, Addition, BoxGroup, and Green Visor Capital.

In this episode, you will learn:

- Kelly Littlepage and Stephen Johnson turned a childhood friendship into OneChronos, a cutting-edge trading platform using combinatorial auctions.

- Their startup journey began with a bold idea: bring computationally complex auction theory into real-time capital markets.

- Early rejection from Y Combinator led to a more strategic, staged approach that ultimately won them entry and shaped their go-to-market thinking.

- Launching OneChronos required not just innovation, but mastering complex financial regulations to build a compliant trading venue from scratch.

- They raised over $80M by finding long-term, high-conviction investors who understood the depth and time horizon of their vision.

- OneChronos sees itself as the foundation for future markets in which algorithmic agents, not humans, drive global transactions.

- Their advice to founders: perseverance and emotional stability are essential in building deep tech companies that take a decade to realize.

SUBSCRIBE ON:

Keep in mind that storytelling is everything in fundraising. In this regard, for a winning pitch deck to help you, take a look at the template created by Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley legend (see it here), which I recently covered. Thiel was the first angel investor in Facebook with a $500K check that turned into more than $1 billion in cash.

*FREE DOWNLOAD*

The Ultimate Guide To Pitch Decks

Remember to unlock for free the pitch deck template that founders worldwide are using to raise millions below.

About Kelly Littlepage:

Kelly Littlepage is a mathematician, computer scientist, economist, and quant trader turned founder. He is the co-founder and CEO of OneChronos. The company designs and operates Smart Markets (mechanisms that match buyers and sellers using mathematical optimization). Its goal is to grow the gross world product by facilitating trade, starting with US Equities.

Raise Capital Smarter, Not Harder

- AI Investor Matching: Get instantly connected with the right investors

- Pitch & Financial Model Tools: Sharpen your story with battle-tested frameworks

- Proven Results: Founders are closing 3× faster using StartupFundraising.com

Connect with Kelly Littlepage:

About Stephen Johnson:

Stephen Johnson is a tech professional with a drive for learning and building. He spent the first phase of his career at Accenture Consulting, where he helped solve some of the most challenging cybersecurity and distributed systems problems large enterprises face.

Stephen spent his last two years at Accenture leading initiatives to bring emerging technologies out of the R&D lab and into the market. More recently, he co-founded OneChronos, an upcoming trading venue that uses AI-powered auctions to solve some of the equities market’s most significant problems.

Outside of his professional career, Stephen spends much of his time coding, running, and embarking on various music-related tech projects. He is a seasoned C++, Java, and Ruby programmer who is now building Elixir expertise.

Stephen is a Colorado native and now resides in Brooklyn, New York.

Connect with Stephen Johnson:

Read the Full Transcription of the Interview:

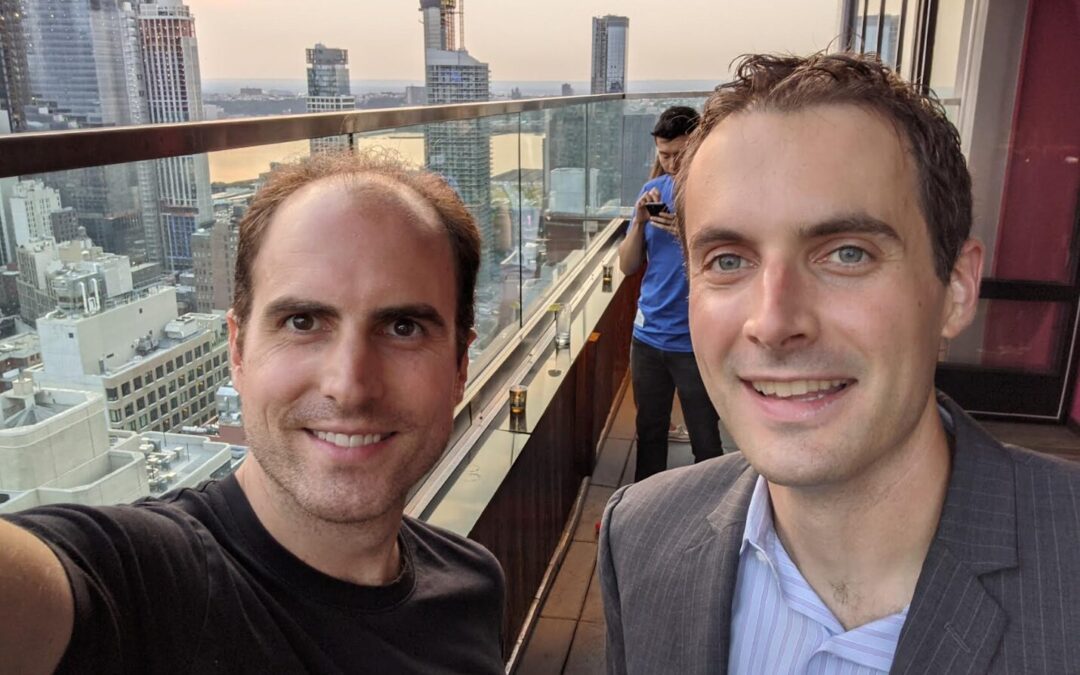

Alejandro Cremades: All righty. Hello, everyone, and welcome to the DealMaker Show. Today, we have two co-founders joining us. It’s quite a remarkable story. They’ve been building this company for a decade now.

And again, some really interesting stuff. They’ve known each other forever. We’re going to be talking about all the good stuff—tackling problems, knowing when is the right time to do so, their Y Combinator admission process, the early days, early signs of life, how they’ve thought about hyperscaling growth, and also about raising money. So without further ado, let’s welcome our guests today, Stephen Johnson and Kelly Littlepage. Welcome to the show.

Kelly Littlepage & Stephen Johnson: Thanks for having us. Hey.

Alejandro Cremades: So, originally born in the south of Denver in Colorado. You guys are actually from the same town and have known each other forever. How was life growing up for the two of you? Maybe we can get started with Stephen and then hear from Kelly.

Stephen Johnson: Yeah, yeah. Pretty unique story. We met each other in middle school. Life was pretty sleepy—we grew up in a quiet suburb. I think we were both pretty bored and spent a lot of time tinkering with computers because there wasn’t a whole lot else to do.

That kind of planted the seed of working with programming languages and learning software development on our own. In the early days, there weren’t a lot of resources to do that. There was no such thing as a computer science class in our high school. So it was very much a “fish for yourself” kind of situation.

We got in a fair amount of trouble with computers in those days—nothing too bad, but like a lot of people in the ’90s and 2000s, it was the Wild West out there in the world of computers.

So yeah, I think it was a very lucky happenstance for both of us that we’ve known each other since childhood.

Alejandro Cremades: And what about you, Kelly? What got your attention with computers? What was it about them that was so exciting?

Kelly Littlepage: Yeah, I’ve just always loved systems in general and figuring out how things work. Computers were a really tangible system you could figure out. I remember when I was a kid, I was fascinated by the way the pump worked at the neighborhood pool and at aquariums and things like that.

At one point, it just kind of dawned on me—hey, the computer must be doing something. This was during the early internet era, and as Steve said, there weren’t really resources or anything low level, so you kind of learned by doing—taking apart hardware and trying to figure out what happens.

As Steve said, the most exciting thing in our neighborhood at the time—and Denver is a very cool place now, but it wasn’t when we were there—the most exciting thing we had was a McDonald’s and some old Packard Bell computers to rip apart. So that’s how I got started anyway.

Alejandro Cremades: And Stephen, how old were you guys when you met in middle school?

Stephen Johnson: We were probably about 12 or 13, and we really got to know each other in high school.

Alejandro Cremades: Do you remember, Kelly, the first day you saw Stephen?

Kelly Littlepage: First day?

Alejandro Cremades: The first day you saw Stephen in your life. I mean, it’s a long time ago—you were 13 years old. I’m wondering, what was your reaction? Was there a special connection back then or not?

Kelly Littlepage: I think we were both pretty different people back then. I was going through a bit of an Eric Cartman phase, which I’m proud to have mostly—but not completely—grown out of. And Steve’s always been pretty buttoned up.

Stephen Johnson: Yeah, I was not the most social kid in those days, so it was probably a very awkward teenage interaction.

Alejandro Cremades: Now for you, Steve—you went to Lehigh University and combined computer science with economics, but then you decided to go the consulting route at Accenture. That was pretty much all you knew until you guys decided to join forces. What was that experience like, working at Accenture and experiencing different divisions?

Stephen Johnson: Yeah, so I went into consulting because I couldn’t decide what industry I wanted to work in or what I wanted to do when I grew up after college. The good thing about consulting was that I got to experience a lot of different industries and see the same problems replicated across different companies—huge companies.

I was working mostly in cybersecurity and software engineering at the time. But my heart has always been in building things. I was a huge Legos kid—probably why I got into computers as well. You can build software, you can build the computers themselves.

Consulting is very much—you go do a project and then hand it off and never see it again. And I didn’t love that. So I ended up moving into an R&D group where I got the opportunity to build new technologies and services from scratch.

This starts to get into the OneChronos story. The big project I was tasked with was building a platform that takes a bunch of data from corporate networks, the federal government, web applications, etc., and tries to find signals that hackers are breaking into the company. It was very much a big data, signals processing, and analytics platform.

It turned out that Kelly was doing similar things, but for markets—trying to find signals to trade better. So I’ll hand it over to Kelly to talk about that. That’s kind of one of the formation stories for OneChronos.

Alejandro Cremades: Let’s talk about that too, Kelly. In your case, you went to Georgia Tech, and then after that, you went to a hedge fund—which is what gave you the exposure Steve was alluding to. Why hedge funds? What caught your attention?

Kelly Littlepage: Yeah, so actually that part of the story starts with my undergraduate, which was at Caltech. I did Georgia Tech while I was working. I got very interested in economics my freshman year—just by complete coincidence. I came into school as a physics major, later graduated doing applied math since I gravitated toward that.

But there was this very cool and interesting intersection of those fields in the world of auctions, which was not something I’d ever thought about or knew about going in.

Again, in the town of Centennial, Colorado, academic auction theory was not being discussed a lot at the time. It was this notion that you can design—just like you can design computer systems—you can design auctions that are aligned with economic interests for agents, as we call them (buyers, sellers, participants in a market in general).

The idea that you can design these systems to produce good outcomes was really interesting. When I graduated, there wasn’t really a lot of opportunity to do pure math outside of academia at that point—or even the applied stuff I was interested in. Finance was a great outlet for it.

I was also familiar by then with the D.E. Shaw story—this idea that, hey, you can go and make money doing something unrelated to basic science and then come back to it later, whether it’s funding or doing research. I really gravitated toward this idea of trying to have some commercial impact and then take that back to academia later.

Alejandro Cremades: So then the computational ability—you guys were sharing and incubating ideas. Eventually, you saw it was the right time. Why weren’t you able to execute earlier, and what sequence of events had to happen before you were both ready to go?

Kelly Littlepage: Yeah, so the type of auction we run is something called a combinatorial auction. It’s not something we invented, and we weren’t the first people to do it. A lot of the confidence we had in building OneChronos as a company came from the fact that these have been so successful elsewhere—whether in display advertising or wireless spectrum licensing.

The problem with these auctions—especially the format relevant to capital markets—is they’re a very, very hard optimization problem. There wasn’t a technical path to do them at the speed and scale of capital markets when I was studying them.

There wasn’t that technical path until the AlphaGo and AlphaZero era, when the same body of research about using machine learning to accelerate search and optimization problems became a real thing.

Steve and I saw this at the time, just by staying plugged into the academic community. We said, “Hey, there’s actually a technical path forward to doing this in capital markets.” That was a big part of the timing story for why we got started on OneChronos back then.

Alejandro Cremades: So what was that day like—when you picked up the phone, you guys were chatting, and it was go time?

Stephen Johnson: Yeah, that’s a fun story actually. We were both at a point where we were figuring out what to do next career-wise. We had talked on the phone a couple times about this idea we’d been working on for a long time and whether or not to go for it.

I flew out to Chicago for about a week, where Kelly was at the time. We spent the whole week whiteboarding the idea—getting into the actual design of the mechanism, what we might do, what problems there were, how we might solve them.

At the end of that week, we both came out of it thinking, “Okay, I think we should try this. Let’s go for it.”

Alejandro Cremades: So then, Kelly, what was the immediate step after you said, “Let’s go for it”?

Kelly Littlepage: Yeah, we started fleshing out the exact go-to-market strategy. As Steve mentioned, part of that week involved talking to some of my former colleagues and counterparties about what they were seeing in capital markets and whether there was appetite for this.

The first thing we had to figure out was how to slot this into existing capital markets. No one else is doing combinatorial auctions the way we are—outside of OneChronos.

That sounds great, but if you’re doing something that doesn’t fit into an existing market structure, it’s very hard to get customers or day-one participants. Capital markets are a big, fragmented space with lots of choices.

If you’re a new venue and don’t have the same liquidity—meaning the same number of buyers and sellers—as other venues, you need to give people a reason to plug into you at all.

There are only so many hours in the day, and these clients have real opportunity costs. You can win on the product side, but you also have to reduce friction as much as possible.

We were focused on both—which was a really big technical problem. That was the first six months of figuring out how to do this. The next question became: how do we fund it? How do we build it? That kind of goes into the next chapter for the company.

Alejandro Cremades: So let’s talk about that, Steve. Let’s talk about the Y Combinator application process.

Stephen Johnson: Yeah, the funny thing about the application process is that it looks very easy at first glance, but you end up spending hours and hours obsessing over each paragraph you write.

Part of what was challenging for us with the whole YC process was… after that six-month period of figuring out what day one would look like, we realized that there was no way to do this without basically building a stock exchange.

We’re technically an ATS—which is like an exchange. But you kind of have to build it all at once. It’s expensive. It’s not something you can do in a few months, get an MVP out there, see how it goes, and fix things as they break.

It’s a hard tech problem—capital-intensive, a lot of time up front—which is foreign for Y Combinator and investors in general.

Stephen Johnson: So our application was, you know, we need five years and $10 million to get this done. And we got rejected the first time we applied because of that. We got a call from one of the partners there after our rejection and spoke to him for a long time—Jared Friedman.

And he kind of gave us some coaching. He was like, “Look, you guys need to figure out a way to get this done, or at least show some signs of life early on, before launching with a lot less capital.” So we came up with a different plan, applied again, and got in that time. That sort of changed our mindset a bit early on about the fundraising process, what it was going to be like, and the steps in between zero and getting to launch.

Alejandro Cremades: What was the before and after with Y Combinator, Kelly?

Kelly Littlepage: Yeah, so Y Combinator is definitely a strong forcing function. I would say for a lot of companies that are in more traditional verticals like SaaS, it’s also a big portfolio of customers coming out of it.

We didn’t have that at all. In terms of what Y Combinator helped us with, it was really shaping the process of building a go-to-market strategy, but not the customers that you’re going to acquire after.

So we did YC, we did Demo Day, we raised our seed round on the back of that, and it was really, “Okay, what’s next?” And what’s next, in this case—as Steve alluded to—is we had to create a regulated market.

Doing so on a startup budget required really learning a lot of the specifics and doing a lot of that application work in-house to control costs. Steve became quite the expert during this period on the nuances of NMS and FINRA broker-dealer applications and a lot of stuff that has proved very useful over time. It’s just a little different from the typical startup motion.

Alejandro Cremades: And Steve, how has the journey of raising money been? I think you guys have raised a little bit over $80–82 million. What has that journey been like?

Stephen Johnson: Yeah. So the journey has been interesting because, you know, we are a capital markets company. And venture capital is also a form of capital markets, right? So you’d think they’re very similar, but the reality is our company is pretty deep in the weeds of the trading infrastructure of the world—really the capital markets plumbing—which not a lot of companies are starting or trying things in.

So it was pretty foreign for a lot of investors. I would say the fundraising process for us was very much about having to find a small number of investors who had very high conviction and some experience in the field we were in. Greenvisor Capital led our seed round and our Series A, and they’ve been a huge part of our success. The time between our seed and Series A was a few years, and then another few years before we really launched.

So it’s a deal where we always knew we needed some patient capital and people who would be with us for the long term. And we’ve been very fortunate that they—and the rest of our investors, including Addition, who has led the recent rounds—are really in it for the long haul. Because this is a long-term company that we’re building.

Alejandro Cremades: Well, talking about the long term, just for the people that are listening, to get it clear—what ended up being OneChronos? How do you guys make money today?

Kelly Littlepage: So right now, we’re a US equities trading venue. As Steve said, we’re something called an ATS—an alternative trading system—which is like a stock exchange. We just don’t do listings. We’re only matching securities for institutional buyers and sellers.

And the way that we match is via combinatorial auction, which is the mechanism that I mentioned earlier that before was computationally impossible. Now there’s kind of a path forward. We started with US equities as a beachhead because it was a way of demonstrating the potential for this.

It’s a very big and very fragmented market. It’s not the final destination at all. Really, the way we see this is that value is created for institutional investors when they’re able to think about portfolio construction and their investment process—and not have to think about the complexities of fragmented market structure.

And that’s what combinatorial auctions give them, big picture.

Alejandro Cremades: So obviously, one thing that comes to mind here is that when you’re raising that money and doing what you’re doing, people are really betting on the future.

I mean, you guys were betting on the future to begin with—already banking on $10 million and five years, right? When it comes to the vision—let’s say you guys were to go to sleep tonight and you wake up in a world where the vision of OneChronos is fully realized—

What does that world look like, Steve?

Stephen Johnson: Yeah, so I think that world looks like a lot of transactions that take place now—for anything, like trying to get a trucking route from Chicago to New York, or trying to sell a bunch of liquid natural gas. Say you’re a shipper in the US and you have a ship full of LNG—what’s the optimal route to take that?

All these kinds of transactions are currently very manual. A lot of them happen through brokers or through a kind of voice trading process.

Our thesis is that a lot of these transactions will at least be facilitated and enabled by algorithmic agents going forward. This is basically how equities markets work now. If you’re a large institution and want to trade a large portfolio or a large percentage of a company, you’re outsourcing that job to a series of algorithms—human in the loop, making sure those algorithms are doing what you expect, measuring performance as they execute trades in the market.

We think a lot of other markets are going to go a similar way—where it’ll be humans enabled by algorithms to do much more than they can currently do and get a lot more efficiency than they currently can. We’ve purpose-built our whole platform to work well for algorithmic agents to do business with each other.

That’s kind of the whole idea behind smart markets in general—at least the form we’re using. And we see that proliferating throughout all kinds of different physical economy markets. And we want to be at the center of all that.

Alejandro Cremades: So in your case, you’ve shifted from the early-stage mindset to more of a growth-stage mentality. Kelly, what does that transition look like?

Kelly Littlepage: Yeah, so there’s definitely the operational aspect of just going live. Before launch, we were largely a pure engineering company focused on just building new technology. Once you’re operational,

You’re constantly trying to iterate, make existing products better, and launch new ones—but you also have to keep a market running with absolute correctness and 100% uptime. There’s a lot of engineering complexity that goes into that task, and that’s more of the day-to-day now.

I’d say that’s been the biggest shift. And then riffing off of what Steve was saying—right now, we’re this US equities market. The bigger picture is about building the bazaar for the AI of the future, where these autonomous agents are going to do business with each other.

A lot of it is threading that right balance between focusing on the immediate growth story—capital markets, and within that, largely US equities—but also staying true to the vision and what the really big opportunity is here, which is this new type of market that we see emerging.

Alejandro Cremades: I want to bring you back in time, okay? I’m going to put you guys into a time machine.

Kelly Littlepage: I like that.

Alejandro Cremades: Let’s say 10 years ago, and it’s that moment where Steve is visiting you, Kelly, in Chicago. You’re starting to really think things through. And I give you both the opportunity of being there with your younger selves.

You have the opportunity to give one piece of advice before launching the business. What would that be and why, given what you know now? Let’s start first with Steve.

Stephen Johnson: Perseverance is definitely the first thing that comes to mind. We kind of knew going in that this was going to be years of effort and grind to get it done.

So it wasn’t a surprise, but in retrospect in particular, there were a lot of times when we could have just given up on the process—and didn’t. And it ended up paying off. That’s by far the trait that for me has been most valuable. A lot of it has come from the confirmation we’ve received along the way—from before we were live, from potential customers, and after we were live, from customers.

What we’re doing is very innovative and exactly what the market needs—it’s just going to be very hard. So yeah, perseverance is what I would say.

Alejandro Cremades: And Kelly, what about for you?

Kelly Littlepage: I have a similar answer but a different flavor, which is basically—the good stuff that happens to you is never as good as you think it’s going to be. And the same is true for the bad stuff.

When you think about perseverance, really don’t celebrate the wins for too long. You should already be thinking about what needs to happen next, what you can do more of, and what you can do better. And when something doesn’t go your way—

It’s really not as bad as it seems at the time. Whether that’s an investor conversation that didn’t go the way you thought it would, a customer conversation, anything.

You just have to have a very level mindset to build a company over 10 years.

Alejandro Cremades: For the people listening who would love to reach out and say hi—what’s the best way for them to do so, Steve?

Stephen Johnson: Best way to reach out to us?

Alejandro Cremades: Best way to reach out to you, to learn more about the company—what’s the best way to do so?

Stephen Johnson: Yeah, in**@********os.com is the best way. And careers—if you’re interested in working on fun deep tech problems and capital markets.

Alejandro Cremades: Amazing.

Alejandro Cremades: Fantastic. Well hey, thank you so much for being on the DealMaker Show today. It has been an absolute honor to have you with us.

Kelly Littlepage & Stephen Johnson: Thank you very much for hosting us. Thanks, Alejandro.

*****

If you like the show, make sure that you hit that subscribe button. If you can leave a review as well, that would be fantastic. And if you got any value either from this episode or from the show itself, share it with a friend. Perhaps they will also appreciate it. Also, remember, if you need any help, whether it is with your fundraising efforts or with selling your business, you can reach me at al*******@**************rs.com

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

Facebook Comments