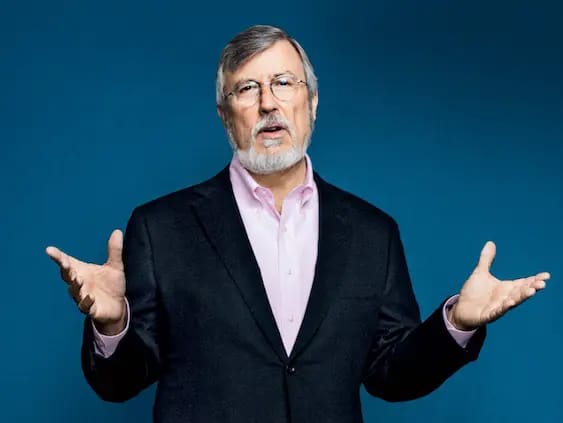

Carey Smith bootstrapped his own startup from zero to selling it for $500M. He is now a startup investor helping others grow their own ventures. He has invested in several startups like Awkward Essentials, Vibrant Gastro, Vibrant, Shotgun Seltzer, Lumen, and Tushy.

In this episode, you will learn:

- How Unorthodox Ventures helps other startups

- What Carey reads, and what it has taught him

- What he thinks is most important in building a business

- The right time to accept funding, and not

SUBSCRIBE ON:

For a winning deck, take a look at the pitch deck template created by Silicon Valley legend, Peter Thiel (see it here) that I recently covered. Thiel was the first angel investor in Facebook with a $500K check that turned into more than $1 billion in cash.

*FREE DOWNLOAD*

The Ultimate Guide To Pitch Decks

Moreover, I also provided a commentary on a pitch deck from an Uber competitor that has raised over $400 million (see it here).

Remember to unlock for free the pitch deck template that is being used by founders around the world to raise millions below.

About Carey Smith:

Every year, entrepreneurs start more than half a million companies in America. Only 200 of them will ever reach $100 million in revenue. Carey Smith knows what it takes. He led Big Ass Fans from $0 to $250 million in less than 20 years. Now he’s breathing new life into the entrepreneurial domain through his Austin-based startup incubator, Unorthodox Ventures.

Raise Capital Smarter, Not Harder

- AI Investor Matching: Get instantly connected with the right investors

- Pitch & Financial Model Tools: Sharpen your story with battle-tested frameworks

- Proven Results: Founders are closing 3× faster using StartupFundraising.com

Connect with Carey Smith:

Read the Full Transcription of the Interview:

Alejandro: Alrighty. Hello everyone, and welcome to the DealMakers show. Today we have a very, very exciting guest, a guest that has done the full cycle himself and actually bootstrapping all along without investors on his big, big exit that he did a few years ago. I find that many of you that are watching and listening are going to find his story super inspiring. So without further ado, let’s welcome our guest today. Carey Smith, welcome to the show.

Carey Smith: Thank you very much, Alejandro. It’s nice to be here.

Alejandro: Originally born in San Diego, and I know that you moved quite early on, but tell us about the upbringings.

Carey Smith: We moved all over the country when I was a child, and for no particular reason, when I think about it or any particular reasons that I’ve known about, I think that when people ask me where I’m from now, or at least as a child, I say, “Most of the time as a teenager, I spent around Washington D.C.” Since that time, I went to school in Chicago and moved again. I’m fairly peripatetic, so we ran a peer after many years in Austin. We started the fan business, the Big Ass Fan business, in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1999. Those are the places that I think are the most important to us, the latter being where the Unorthodox Ventures or VC firm is located.

Alejandro: We’ll walk through those in just a little bit, but rewinding back a little bit more in time when you were in those early years, you thought that perhaps going to work for somebody else was the way to go, and you actually got into the insurance business. But you also got out of it very quickly, so what happened there?

Carey Smith: I always think that I can work for other people, and I really think that I can. Maybe that’s not true, though, right? I had always thought about starting my own company. After working several years in the insurance business, there was no particular reason; it was not especially interesting. It was relatively boring. I was in my 20s. I wanted to do something interesting. Insurance isn’t especially interesting. So I decided, not knowing any better. What I did was I went home one day and asked my wife if I could sell the house. She said, “Sure.” We did, and we started the business.

Alejandro: I know that the first business or the first path or journey into doing your own thing was building a company with your own father. I know that the outcome was perhaps not the one that you would have hoped for, but I’m sure that it was full of lessons, so how was that for you?

Carey Smith: I think the most important lesson is that you probably shouldn’t go into business with your father. [Laughter] Other than that, I learned quite a bit. It was quite interesting, simply because my father had no real experience in business, and so I had to learn it more or less from the ground up. I had to get involved in sales and marketing, and I had to write a lot of articles; I did a lot of research. It was great, though I wouldn’t suppose that anybody else wanted to do it. I certainly wouldn’t recommend it because I think I had three or four years of learning, though it took me 12 years to do that. So it was, all-in-all, kind of a waste of time. Though, it put me in a situation for good or for bad where I couldn’t do much of anything else other than start another business. But, again, you learn a lot when you’re doing it yourself. We didn’t have any money. We had to do everything ourselves. I guess it was a good education in regard to that because I certainly knew how to do it after that.

Alejandro: What was that key takeaway out of that experience that you knew that you would definitely apply to your next company?

Carey Smith: I think the main thing is that you have to know your audience. You have to know your market. The one thing that I took from the first company to the fan company was the knowledge of the industrial facility market. I certainly knew what the problems and who the players were in the specific facilities. That was a big part of why we were successful with a fan company because we knew everybody. I don’t mean individually, but we knew who our admirers were, what their interests were, what their concerns were, what their budgets were, which made a big difference in being successful.

Alejandro: In your case, after this experience with your father, you were appointed to your next company. How did you come across the idea, and what was the process of bringing it to life?

Carey Smith: As I said, one of the things I did a lot of, from the beginning, was marketing, and a lot of the marketing—because we couldn’t afford to go outside ourselves, we did the marketing in-house. I did a lot of research; I wrote a lot of articles, and I knew a lot of editors in various publications. This was pre-internet, so it was a situation where you could actually get to know the editors, and editors have problems of their own with the various trade publications. They were always looking for articles. They were always looking for content. They call it filling the news holes so that they can sell advertising. I think I was able to take that. I don’t know if it’s something—well, I guess it did come from the first company because it was the desire or the acknowledgment of the fact that you have to educate people, especially as it relates to what we were working with, which was the evaporation of water in the first company, and then air movements and human physiology in the Big Fan company. Those were what we concentrated on, and that’s what I was able to bring to the fan company, and that worked to our advantage.

Alejandro: This, obviously, was what led into Big Ass Fans, your biggest success to date. Tell us about Big Ass Fans. How did you come up with the name? What an interesting name.

Carey Smith: Actually, I didn’t come up with the name. When we started the company, we initially called it HVLS Fan Company, High Volume Low Speed Fan Company. What we did was we had a very, very large diameter fan. We’re talking 20-24 feet in diameter. It was powered by a 1.5-2 horse-power motor, so a very low power fan. It moved very slowly, but it moved an incredible amount of air. The HVLS was a good descriptor, we thought, but inevitably when somebody called us on the telephone, a potential customer, we would say, “HVLS Fan Company,” and they would respond with pause and say, “Are you those guys that make those big ass fans?” We’re not the sharpest knives in the drawer, but we thought, “That’s a much better name.” [Laughter] So we changed the name of the company. Again, I’ll tell you what’s interesting about that is, you have to listen to your customers, and we did in that case. But what was funny about it was we got an awful lot of pushbacks, which, again, is just attention, and it was funny to get the pushback. I think it defined, in a lot of senses, the culture of the company, which was—I mean, we worked at this very hard. We continually developed new products, new markets. It was a lot of hard work, but at the same time, we didn’t take ourselves too seriously, and I think that was indicated by the name. There were some people that didn’t like it. We used to receive a lot of letters telling us that we were going you know where, but on the other hand, there were a lot of people that thought it was funny and applauded our moxie, and there are a lot more of the latter than the former, so it worked.

Alejandro: What was the business model of the company? How are you guys making money and all of that stuff so that the people that are listening really understand the model there?

Carey Smith: We did everything ourselves. Again, maybe that’s something I took from the first company. We actually manufactured the fans we sold. Literally, put them all together, designed them, constructed them, sold them from our factory in Lexington, Kentucky. That’s where everything came from. Though we tried various forms of distribution, inevitably, what worked the best and what we finally settled on was selling it ourselves. So we hired salespeople, sales managers, and we distributed them throughout the country, and they sold the product. On the marketing side, we did all the marketing ourselves. We wrote everything ourselves. We place all our ads. We designed all of our ads. Everything that we did, we did ourselves. When we went overseas, we purchased a motor company to manufacture a residential fan. We wound up manufacturing that residential fan in Malaysia at a plant that we owned with our people. We distributed to the Far East via that plant. But, again, I think the main takeaway is that we did it ourselves. As you mentioned before, it was bootstrapped. So I think that it differs in quite a number of ways from a lot of companies that we see ourselves today because they have a tendency to want to have other people do the design, the manufacture, and a lot of times the manufacture goes to China. It’s second-rate. The Chinese, if it’s a good idea, will take it from you. That’s the way it works regardless of your IP. I think that doing everything ourselves in the States allowed us to bring up the product very strongly. We had 200-something patents, but I think the patents were much less important than the branding of the company, and a lot of that had to do with 1) manufactured in the U.S., 2) in terms of customer service, if we made a mistake, we took responsibility for it. We were very open about it, not only with the customer. We were very open with and it with the people that worked at the company to let them know that it was fine to make a mistake; you simply had to take care of it. You had to make sure that the customer was well taken care of. In addition to that, if you expect the best customer service, you’ve got to have exceptional employees. We paid our employees 30% more than was typical on average. In the U.S., 40% more than was the average in Kentucky. When I think about business, and I think about the way to run a business, the way it all comes down, it’s not that complicated. You’ve got to be transparent. It’s the golden rule. Treat everybody the way you would want to be treated, and in the long run, it works out. It’s karma. That’s the way it is for us, and that’s what I would suggest. That’s what I’ve learned.

Alejandro: Why didn’t you raise any money, Carey? Why did you bootstrap this all the way to the exit?

Carey Smith: Well, the reason was that in 2017, I was written a check for $500 million, and it belonged to me. It didn’t belong to anybody else, and I was able to do with it as I pleased. There were a couple of things going on there. We didn’t raise money because, honestly, I was a financial illiterate, and it never occurred to me. During that time, it just wasn’t what people were talking about. I don’t think I would have done it anyway. I hope I wouldn’t have done it because I don’t know that it would have helped me, at least me personally. I think that being on the other side of the table, the thing that money can do for you, but you have to be very careful with it, because it’s easy to spend, and you are trading equity for it, is that it can speed up the process if you know what you’re doing with the money. If you don’t know what you’re going to do with it, and if you spend it poorly, then it’s a total waste. We know a lot of people; we talk to a lot of people that have companies, and actually collected over the last year and a half about 40 of them where the founders had less than a majority of the equity, and a significant number of them had their equity holdings in the single digits, which I think is close to a crime. It’s certainly not a place you would ever want to be because most of these businesses aren’t worth that much. Even in the best scenario, they wouldn’t be worth that much, so I say, “Worth what?” Worth $100 million; they’re not worth that. But even if they were, if you had started a business and sweated through everything, and at the end of the day, you sold the business for $100 million, and you only had 6%, that’s not such a big deal. That’s just not where you want to be. Though I am a proponent of funding businesses to a degree, but only when they know what they want to do with the money and they spend it wisely. Most young businesses don’t have a very good business plan. That’s something we try to help them with, but it’s easy to do that. It’s like getting a tattoo on your forehead. It may seem like a good idea at one point, but you’ve got to live with that stuff. If you’re successful and you have an exit that’s reasonably good, you’re simply not going to walk away with a whole lot of money. You have to keep that in mind.

Alejandro: Of course. I think that also it depends on who you’re raising the money from because in some instances, it’s all about having sophisticated people that can lift up the phone and help with distribution, with subsequent rounds, with whatever that is. But I’m right there with you that I think that at an early stage, founders need to also think about their own exit versus what’s going to be the company’s exit. I see it many times where you see a company selling for $450 million, and you see the founder walking away with nothing. That’s really awful to watch. In your case, Carey, the acquisition—how did it come about? What was that process like, and how big was Big Ass Fans at that point?

Carey Smith: It’s interesting. As anybody that has started and run a company knows, you have those days where you go, “Oh my gosh! I’m just tired of this. This doesn’t make any sense to me.” I happen to have been very vocal about it on one particular occasion. I had a fellow that had come in as my CEO, maybe six to nine months before that, but he had come in, and he had held positions in large corporations. He said, “Really, Carey? Is that really true? Would you actually do that?” I said, “Well, for 500 million bucks, you bet I’d do it! He said, “We can do that if you wanted.” I said, “Yeah, fine.” I really didn’t think too much about it, but he actually went out and made some calls and started bringing it together. It took about a year, all together, but at any point in time, I think what made it interesting was, I was more or less ambivalent about it. My wife didn’t believe it for one second, not even one second, that we would sell the company because when you do something for that long a period of time, most people don’t think about shifting. I certainly wasn’t thinking about that. But as it progressed, it got more interesting. But at the end of the day, we had some disagreements with the PE firm, and as you will; that’s normal. They came back with a lower number, and I said, “You can just hang it. I really don’t care because I want what I want, and I don’t want anything less than that, and that’s it.” And that was true because I really didn’t care. I think that when you’re looking at a situation where you’re looking to sell your business, that you have to be in a situation that you are ambivalent because the people that are looking to buy your business have done it more than once, and you may have only done it once. They’re very adept at trying to talk you down and buy it for just a little bit less, and you have to be of the mind that, “No. That’s it. I don’t care. End of story. Get out of my life.” I think that was important, and that’s the way it worked for me.

Alejandro: I’m right there with you. I think that being in touch with the outcome is the way to go because that’s definitely going to send a message to the people across the table. In your case, Carey, what was it like when all of a sudden, you see on the table a check for $500 million?

Carey Smith: It was kind of cool. I’ll tell you what was cool about it, which was that I had for ten years prior to selling the company established this SARS program, which is a stock option, fan stock because we were operating in Lexington, Kentucky, which is an okay little town, but most people don’t want to move there. It’s pretty, but that’s about it. I did that in order to attract talent and also to award the people or reward the people that were the best workers. All of it was great, and we were valued every year, but I thought in the back of my mind that even though people got these shares, it’s like, “Yeah, whatever. We don’t know what they’re worth. Nothing’s ever going to happen because all Carey talks about is a 200-year company.” I thought, “It would be nice to be able to get to a point where the number was big enough so these people could actually say to themselves, “What a deal! I made a great decision in coming to work here. This is going to work out for me.” I thought that $500 million was a good number. As I mentioned before, as we were talking that we made, of those people—there were over 1,000 people, at one point, that were working in the company, but there were about 150 that actually were—and if you run a company, you know this. You can have a lot of people, and a lot of them are nice people, but 150 out of 1,000 is about what you would expect in terms of being exceptional. To take that money, the $50+ million, and give it to these people, I don’t think they expected it. They knew it was coming after the company was sold, but almost every single one of them told me that it was going to change their lives, which was cool. I don’t know if it did or not, but there were 15 of them that were multimillionaires and 15-16 more that were millionaires, and the rest were less than that, but it was everybody. There were people driving forklifts that walked away with $70-80,000. A number of these people started their own companies, which was my hope that they would see that this was a path, and hopefully, that they would, in turn, do the same sort of thing for the people that worked with them because being successful is a lot of work, but it’s also luck. It’s just a way to pay back. I thought it was cool, and that’s the best thing that, in my estimation, sitting there looking at $500 million. That was right before Uncle Sam walked in the room. When Uncle Sam walks in the room, then it’s not $500 million anymore. [Laughter]

Must Read: Malte Horeyseck On Raising $130 Million To Acquire Amazon Sellers

Alejandro: Yeah. I hear you.

Carey Smith: That was the coolest part of the whole thing. Honestly, it doesn’t make that much—it’s easy to say, but the difference in terms of—you don’t think about it every morning, and it’s not really that important. What you do with it is what makes it important.

Alejandro: 100%. Now, talking about the next chapter, you’re running your own investment-type of operation via Unorthodox Ventures. Why did you decide to go on the other side of the table and do investments, and what are you guys doing there?

Carey Smith: You spend a lot of time in manufacturing and building a company, and I think that you recognize that there are other people that are very talented that are doing the same sort of thing, and you remember. The way we did it was self-financed. It was very difficult, and we also recognize that the money wasn’t the big part of this. As you mentioned before, it’s the help. When we look at this, and we look at the typical VC, the typical VC is a banker. The only people that know less about business than bankers are lawyers, so we recognized that we can help these people step by step starting business. Normally, the people we talk to really don’t even have a business plan. With a business plan, you have to have a strategy, but very tactical like what do you do? How do you do it? Where do you go? Who are the people you need to hire? What do they need to know? All of this, they need as quickly as they can possibly get, and they’re very ill-equipped to 1) make a plan, 2) execute. What we do is we build the plan with them. We build the plan to break even because we’re not breaking a plan to Series A, Series B. Raising money is really not business. What our goal is, is to build the business so they can get to break even and actually have an operating business so that they don’t have to raise more money. We do that, and we do that with the intent, and so far, we’ve been successful with it, making sure that the founder maintains the majority of the equity. I think that’s being fair, and I think that’s something that a lot of VCs—because I don’t know if they would even think about it or not. It’s not their mindset. It’s not business. But with us, in essence, we have become the C-suite of our group. We’re just a bunch of operators. The majority of the people here came from the fan company. They’re engineers, software guys and gals, and they’re people that opened offices, people that were project and product managers, and we can offer that help to our partners and then help them hire the staff that they need to do that so that we can step away and they can actually have a business and feel good about it, and we can feel good about it as well. It’s a slightly different model.

Alejandro: There’s one question that I want to ask you here, Carey. Imagine if I had the opportunity of putting you in a time machine and taking you back in time, and you had the opportunity of having a chat with your younger self that was thinking about starting a company. Maybe it could be Big Ass Fans or the first company that you did with your father. If you had that chance to have a conversation with your younger self, what would be that one piece of business advice that you would give to your younger self and why given what you know now?

Carey Smith: That’s interesting. I think that the one thing that has come out of both sides, both businesses, and what I’m doing today is market research. When we started, and I think this is true of a lot of founders is that you imagine that you know the market, that you know what people want, that what you say is the way it’s going to be. In fact, that’s not true at all. I know I thought that way. I thought that way until I developed the fan that we had spent several years on that was a complete bust—total bust, and I really did think this was the end-all, be-all of fans. It was a big commercial fan. I think that what we spend a lot of effort on today and with the companies, even larger companies, is focusing on market research because what you think is right is not necessarily right, and you can make huge mistakes and waste a lot of time and money if you don’t understand the market and if you don’t understand what the market is actually interested in. There are a number of ways of doing that, but in essence, you really do have to talk to the customer. You have to talk to the customer about the experience. So many people we find today imagine that they don’t really have to talk to anybody. If it’s liked or if they get approval, then that’s enough. That tells them all they want, and that’s just not the way it is. It takes a little bit of time, and it takes a little bit of money, less money than you think if you do it right and do it yourself. You can’t focus on, “Do you really want my product?” That’s way too big. You have to focus on small questions, but you can learn an awful lot and save an awful lot and actually get to the market much, much faster. I don’t know how I would have executed it, but if I could have used it, that would have been very important. That would have made a difference.

Alejandro: What would you say, Carey, has been a book that you would have read sooner?

Carey Smith: I want to tell you something. I do not read business books. To me, that’s like reading a book about how to golf. I think golfing is interesting. I don’t do it very often because it takes so much time, but ugh, no. [Laughter] Books—I read a lot, but I read a lot of history.

Alejandro: As they say, history repeats. So in terms of history, is there anything that you’ve read in that regard that maybe you found interesting to the way that you are analyzing things and applying that perspective.

Carey Smith: I don’t know. The thing you learn from history is that there’s a very large number of people that have a tendency not to think about what’s going on and what the future is. What that means from a marketing perspective is that you’ve got a lot of material to work with. If people actually paid attention in the main, if people actually read, if people actually understood history and their own history, the history of their own lives, I think marketing would be much more difficult. I think marketing is a challenge. It’s intellectual chess. That’s what I would take from history is that people typically, and you’re right, it may not repeat itself, but it rhymes, and people don’t pay attention to that, and so they have a tendency to fall and make the same mistakes over and over and over again. That’s life, unfortunately. I’m sure we’ll live through another pandemic.

Alejandro: Oh, for sure, unfortunately. Carey, for the people that are listening, what is the best way for them to reach out and say hi?

Carey Smith: I think it’s easy to go to the website: unorthodoxventures.com. Once you do that, then we can talk on the phone. I’m very open, I think, because, again, I feel like starting and running small businesses is very difficult. I talk to people all the time. I just talked to somebody yesterday afternoon, and I think it’s useful. That’s one thing I wish that I had been able to hook into. It would have been more of that and not talking to the president of your local bank. What does he know about anything? But somebody that’s actually doing something that relates to what you’re doing or has done it and can actually talk to you about tactical problems. I don’t mind talking to anybody about that. You owe the community that. I certainly think I do.

Alejandro: Amazing. Carey, thank you so much for being on the DealMakers show today.

Carey Smith: Thank you for giving me the opportunity. I appreciate it.

* * *

If you like the show, make sure that you hit that subscribe button. If you can leave a review as well, that would be fantastic. And if you got any value either from this episode or from the show itself, share it with a friend. Perhaps they will also appreciate it. Also, remember, if you need any help, whether it is with your fundraising efforts or with selling your business, you can reach me at al*******@**************rs.com.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

Facebook Comments